Sustainability in wine is finally gaining attention around the world. Vineyards and what happens in them are so integral to the way we look at a wine, from quality to style, that the focus on sustainability has naturally had its stronghold there. However, we are increasingly broadening our vision to analyze the full supply chain of wine from the ground to your glass. In this process, one topic has emerged as key to a wine’s...

Let’s dive in.

Heavy bottles do not mean better wine. I promise.

The primary obstacle to overcome is one you, as a consumer, can help us with: The long held assumption that a heavy wine bottle means a higher quality wine. If you pay a hundred bucks for a prestige Napa Cab or Mendoza Malbec, many consumers want the piece it comes in to be heavy enough to use for weigh training even once empty. Not only is the connection between bottle weight and wine quality a fallacy, it is terrible for the carbon footprint of the wine itself.

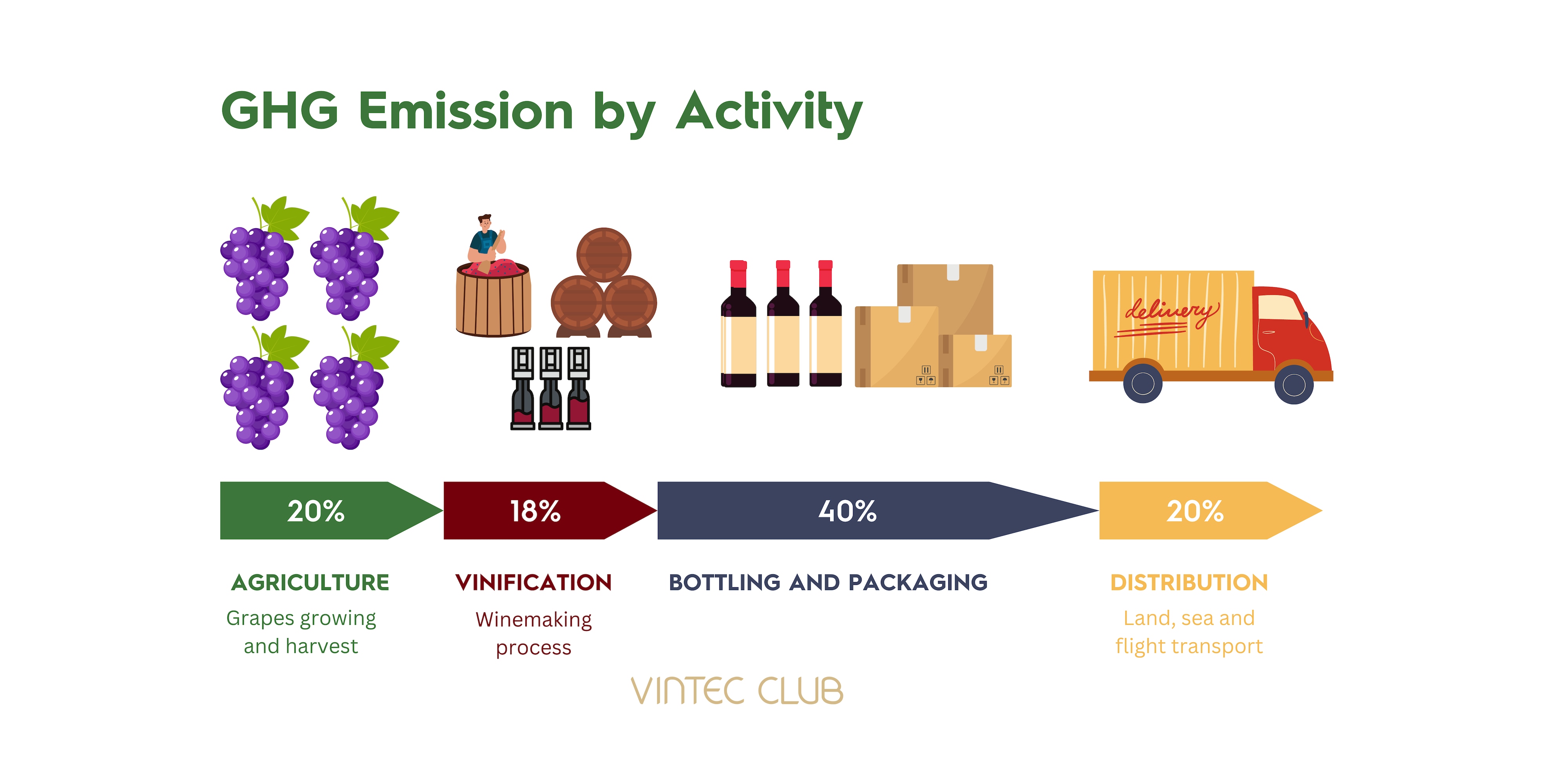

An average glass bottle contributes to a whopping 40% the wine’s total carbon footprint. We can reduce this significantly with lower bottle weights. A standard bottle would be one weighing 540 g (19 oz), a “true” light weight wine bottle will clock in below 420 g (15 oz) and the heavy pieces come in over 700 g (25 oz) up to a nutty 900 g (32 oz). While light weight bottles used to have a high breakage rate, that is no longer the case and there really isn’t any reason for any bottle to weigh more than 500 grams, other than as a marketing move to meet consumer preference. Champagne bottles are the notable exception as they have to withstand the pressure equivalent of a bus tire.

The carbon footprint of a wine bottle is split between production and transportation. The further it has to travel, both to the winery and from the winery to you, the more that weight matters. (Funny enough, the total distance can be less impactful than the mode of transportation - long distances by ship can have the same or lower carbon footprint than a bottle that travels by truck across Europe or the USA). But even if the glass producer is right next door and all your sales are from the cellar door, a heavier bottle takes more energy heat to produce than a lighter one.

Glass has a huge advantage in that it is infinitely recyclable. However, to be recycled into a new bottle, the used glass still has to make it back to the glass manufacturer. Recycling rates vary a lot between countries, with the highest numbers in Scandinavia (shoutout to my homies!) at 97-98%. In my adopted homeland, USA, only a third of all glass bottles overall make it into recycling and not all of this actually goes to making new glass - a fair amount is used as fill for new roads (read more here) In Europe the number is on average 74% and in Australia 46%.

In Australia it is recorded that 46% of consumed glass bottles make their way into recycling.

To summarize, there is ZERO necessity for a good wine to come in a heavy bottle.

Bottles as light as 400 g are now strong enough to hold up in transportation and let you age your wine just as well. Of course, it is more important to drive light weighting in the wines we frequently consume, which means the volume wines you might buy in a grocery store. But consumers making the mental connection between bottle weight and quality is what keeps many wineries hesitant to change to lighter bottles at any price point.

Want to help drive the change?

Keep this in mind when selecting your wines, and feel free to reach out to your favorite winery, big or small, and tell them that you wouldn’t mind a lithe iteration of their packaging. Your added bonus will be less weight to schlepp home from the bottle shop and less weight to carry to the recycling bin. |

While changing bottles to lower glass weights will probably be the most impactful step for the wine industry overall, there are other options as well. The glass bottle for wine won’t disappear in my lifetime but there are other formats out there with a much reduced carbon footprint.

Pop a can at your next backyard BBQ!

My favorite among the so called “alternative packagings” are the cans. Just like glass, aluminum is infinitely recyclable and inert, meaning it won’t interact with the wine and change it. The carbon footprint of a can is approximately 70 percent lower than standard glass bottle per litre of packaged wine. It’s a light, convenient format that - while not for the purists - is actually quite attractive to a younger group of wine consumers. Gen Z and millennial wine drinkers in general are more concerned about the environment and less concerned with adhering to stuffy tradition.

I am older than those demographic groups but have been sold on the format. It’s time to drop the connection between cheap wine and cans. The coolest products in this category are good enough to show up in the hands of both top sommeliers and wine writers. Just look at these suave cans from Swedish start-up Djuice. Djuice isn’t a wine producer but a brand - they create collabs with sustainable wine producers, putting quality, quaffable wines into cans with cool designs by select artists. They look great, taste great and feel like a fresh iteration in a category resistant to change.

Canned DJUICE wines, a Swedish brand established with the goal to provide great wines while saving the environment. (Photo from www.djuice.com)

The plastics conundrum

Other options with a fraction of the carbon footprint of glass include Bag in Box (BiB), PET and pouch.

As a sustainability professional plastic rubs me the wrong way, but I still can’t deny that these formats can have a huge impact on the wine’s carbon footprint and are gaining in popularity. Box wine for example shows a whooping 84% lower carbon footprint than glass bottles! While quality wine in BiB has been available in the box-friendly Scandinavian markets for a long time, winery Tablas Creek made waves in the USA this spring with the release of a super premium 99 USD box of rosé (3 litres = 4 standard bottles) that nevertheless sold out in minutes. BiB is the most popular alternative format by volume, with over 50% of sales in Scandinavia and almost 50% of supermarket wine sales in the otherwise traditional French wine market. Several super trendy natural wine producers including Rhone icon Eric Texier have instead taken the step to pouch, which comes with the same convenient “tap” as a box but in a smaller volume and without the cardboard.

The soft plastic pouches in BiB (generally 3 litres) and pouch (generally 1.5 litres) can be recycled a couple of times. Correct recycling isn’t as likely as we would like though, or available for this type of plastics in all markets. PET bottles, which can be shaped like your standard wine bottle like this one from Lindeman’s does have a higher potential for recycling as the plastic’s quality doesn’t break down as quickly. The coolest ones from a climate perspective might be the flat packs that take up a whooping 40% less space in shipping. Moet Hennessy launched their first flat PET rose in the bottle and gave it the added bonus of being made from plastic collected in coastal areas.

Moet Hennessy’s Provençal rosé in flat plastic bottle.

Wines packaged in any type of plastic are meant to be consumed quickly, not stored or cellared, as plastic lets a decent amount of air through. A Bag in Box has a supposed shelf life of at least six months but the changes begin earlier than that so drink these fresh!

If you enjoy those convenient formats, know you are doing something good for the climate. Just make sure you get your plastic into the correct recycling receptacle to keep it out of landfills and our oceans!

Closing the loop

Because I am still partial to the glass bottle, the most exciting development, that we still only see a few companies slowly venture into, is actually a step back in time. When I was growing up in Sweden in the 1980’s, school kids would collect wine bottles from their parents to bring back to the wine shop for a significant deposit. Bottle reuse has also been standard in many European wine regions where you could even bring a bottle or demi jeans by your local producer for a refill. A more structured system of bottle returns, like the one tested by Loop at Tesco in the UK, can be exciting for both resource preservation, waste reductions and lower carbon emissions. A glass bottle can easily be washed 30 times before needing to be broken into cullet and recycled. Conscious Containers in Sonoma is setting up some early pilots for the USA which show potential.

As long as we can get the consumer on board, maybe bottle reuse is the final solution for sustainable wine packaging. Until that is broadly available however, I’m weighing my options at the wine merchant (literally) and weeding out the heavy pieces. In addition, I’m letting the occasional funky can spice up my wine cabinet. Any winery talking sustainability definitely needs to move away from the formerly trendy heavy bottles. I’d like to think that a producer that is aware of the impact of bottle weight is likely doing good work in the vineyard and winery as well. And that is the kind of soil-to-grape-to-glass view I want from a winemaker. I just have to buy real weights for my strength training from now on.